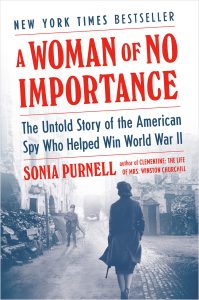

A Woman of No Importance—The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II

Sonia Purnell (Viking, 2019), 368 pp.

Reviewed by Craig Gralley

Sonia Purnell’s biography of Office of Special Operations (OSS) and CIA clandestine officer Virginia Hall, A Woman of No Importance, is by far the clearest, most comprehensive review of Virginia Hall’s life to date.[1] It is a fine exposition that deserves to be on the top shelf of intelligence literature.

Purnell, a former investigative journalist, undertook the formidable task of piecing together an account of Hall’s wartime espionage from the fragmentary government record which formed the backbone of her story. While many lesser agents publicized their wartime exploits, Hall remained the model undercover agent. She shunned the spotlight and stayed true to her secrecy agreement long after her career in espionage ended. She wrote no memoir, granted no interviews, and spoke very little about her clandestine life, even with her closest friends and relatives. Overcoming this absence was a daunting challenge: important documents on Hall in the US archives were missing—possibly thrown out—and the British and French archives suffered fires that destroyed much of the history of agent operations in WWII France. Consequently, key pieces of Hall’s complex story—the tissue connecting intelligence officers, intelligence circuits, and codenames—are gone.

By necessity, large gaps in Hall’s life and career had to be filled with interviews, the memoirs of other agents, and duplicate documents that somehow escaped the calamities of time. Purnell took great pains to marshal what remained and broke new ground by persuading the French government to open sealed files on one of Hall’s key agents—brothel owner, Germaine Guerin. Still, this only took Purnell so far. In a complex story like Hall’s, where large sections of her private and clandestine life are missing, the author was faced with the biographer’s dilemma: stay silent where no information exists, or take an informed leap. It’s here where biography moves beyond description to become a creative process.

Purnell proves to be a master at filling the gaps that swirl around Hall in WWII France, but she is strangely silent when it comes to the interior Hall, leaving the reader to infer Hall’s personality and, by extension, her thoughts, and motivations. This is where a greater grasp of espionage could enrich readers’ understanding of Hall’s actions and offer insight into the personality of a wartime clandestine agent. Purnell’s understanding of espionage reveals itself when she makes the exuberant claim that her research pushed through, “nine levels of security clearance and into the heart of today’s world of American espionage.” This is an odd comment on several levels. Perhaps Purnell means nine levels of classification (of which there are only four). Even then, her comment doesn’t acknowledge that OSS records have been declassified—as have the CIA records she reviewed—so there’s only one level of classification she broke through: Unclassified.

A case-in-point is Hall’s reason for returning to France a second time in the spring of 1944. This is important because Hall’s single-minded passion to do so without regard to the dangers—the wanted posters still in circulation, the bounty on her head, while Gestapo Chief Klaus Barbie still was hunting her—epitomizes the depth of Virginia Hall’s courage. The book is not clear on why Hall returned but in subsequent interviews, Purnell takes a leap: “[Virginia Hall] wanted to prove what she could do. . . . It was her accident that drove her every day.”[2]

Purnell’s exuberant proclamation is appealing because it’s easy to understand. But it’s a conjecture made without evidence or considering the mindset of a clandestine agent. There’s no public record of how Hall felt about the loss of her leg, much less to tell us that her disability was, as Purnell suggests, the controlling force in her life. Moreover, the evidence suggests the contrary, that Hall, a confident, strong-willed, risk-taker, had moved beyond negative feelings of self-worth that required continual affirmation.[3]

While Hall’s motives for returning undoubtedly are complex, she clearly was a driven person prior to and following her hunting accident. Still, the strongest case can be made that Hall returned to France not only because she believed she could make a decisive contribution to the liberation of the country, but she went back out of concern for the safety of the agents she left behind. While Purnell makes a fleeting reference to Hall’s likely feelings of guilt, it is the nature of the case officer-agent relationship that offers the strongest argument for Hall’s return.

The personal bond between the clandestine officer and agent, forged under the most demanding life and death situations, is inordinately strong. Hall broke that bond when she fled Lyon and left her agents in the middle of the night in November 1942 to escape the Gestapo. Her circuit, Heckler, had been blown and she knew her agents would be rounded up and tortured simply for knowing and supporting her. It is the kind of knowledge that can cause unbearable stress and remorse—feelings that could motivate a second return to France.

Was it a coincidence that when Hall returned, it was back to the Haute Loire where she left her agents? Perhaps, but what’s undeniable is that immediately after she completed her wartime mission, Hall undertook what some might consider the unusual step of conducting an extensive 1,000-mile search to find those she left behind. And she did find her agents—nearly all of whom had been sent to prison camps and tortured for assisting her. What’s more, when she saw the pitiful physical and financial condition they were in, Hall, likely feeling responsible, successfully petitioned the US government for financial compensation and recognition for her agents’ valuable service.

One important aspect of biography is the background authors bring to their subject. Sonia Purnell is an exceptionally talented journalist and writer. A few overly exuberant statements and omissions do not dim the remarkable research that went into writing A Woman of No Importance. The book is an important addition to intelligence literature on Virginia Hall and WWII France. It should be close at hand for the intelligence professional, historian or layperson interested in learning more about the life and clandestine career of this heroic disabled American hero.

[1] Large portions of this “untold story” have, of course, been told before but not in such detail or clarity. Two other biographies about Virginia Hall have been published: Wolves at the Door (Judith Pearson, Lyons Press, 2005) and Le Espionne, Virginia Hall (Vincent Nouzielle, Fayold, 2013).

[2] “Morning Joe,” MSNBC, 23 May 2019. Hall lost part of her left leg in a hunting accident and received a wooden prosthesis she nicknamed “Cuthbert” in 1933.

[3] In a 20 October 2015 interview, Lorna Catling said “nothing daunted” her aunt Virginia. As for the need for affirmation, Hall shunned ceremonies honoring her achievements.